2008 Catherine Hoover Voorsanger Writing Prize

The Catherine Hoover Voorsanger Writing Prizes were generously endowed by Voorsanger and Associates, Architects. Each prize was given at the end of the academic year for an outstanding paper on a subject in American architecture, landscape or urbanism written during the academic year. One prize was awarded to a student in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation; the other was to awarded to a graduate student in the Department of Art History or to an undergraduate at Columbia or Barnard College for a senior thesis. Each prize carried an honorarium of $250.

___________________________________________________________________________

Recipient: Karen Kubey, M. Arch '09

The Irrigable Desert and the City on a Stream: The Utopian Socialist Visions of Job Harriman and Alice Constance Austin

Written for Prof. Mary McLeod’s course, Urbanism and Utopia

In 1914, forty‐five miles north of Los Angeles in Antelope Valley, Job Harriman founded Llano del Rio on a faith in the land and a belief in the collective. The colony grew out a distinctly Californian brand of Socialism that focused on individual expression within a communal framework. Alice Constance Austin, an architect and intellectual member of the colony, put forth a plan in 1916 for Llano to develop into “A Socialist City”; later she expanded on her plans in a 1935 book,The Next Step. Where Harriman organized Llano to reflect his colonists’ focus on community, Austin developed introverted housing designs to emphasize residents’ individual privacy. The colonists of Llano invested everything into Antelope Valley’s “irrigable desert” counting on the land to deliver food, shelter, and power beyond what it could ultimately provide; the colony would disband just three years after its birth. Austin understood the importance of working with the natural landscape; she used her designs to argue that adapting to the land and investing in the collective would lead to great benefits for the individual.

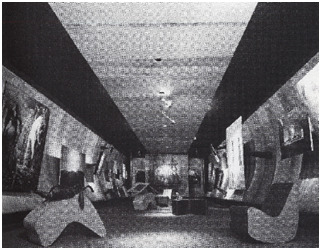

Austin presented her plans for the development of Llano to colonists on May 1, 1916, the two-year anniversary of the colony. In October of the same year, she wrote in the Western Comrade of her vision for the Socialist City. Her city plan was never to be built, as the colony folded before her designs could take root. In 1935, had the opportunity to convey her ideas to a larger audience, with the publication of The Next Step . . . Decentralization . . . How It Will Assure Comfort for the Family – Reduce Expense – and Provide for Future Development.

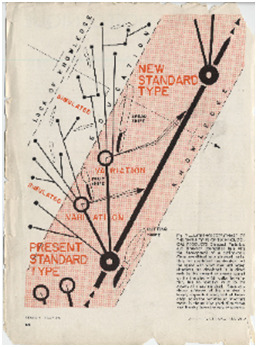

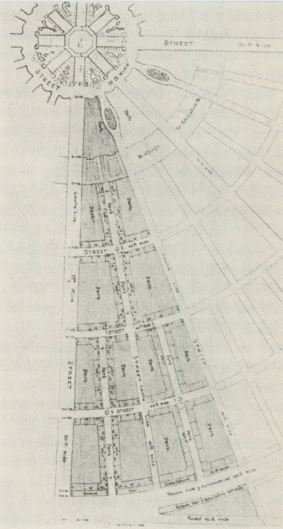

Like her predecessor, Leonard A. Cooke, the author of the 1913 Llano city plan, Austin created a plan for Llano based on spokes emanating from the town’s public center. Her plan established a level of uniformity in its radial blocks and an intelligence in the architecture’s relationship to the Southern Californian climate. “When we say that the Socialist city must be beautiful we wish to draw attention to the fact that we cannot follow the ordinary individualistic plan of allowing each person to build to suit his own fancy. … There is the wider application of fitness, that the situation, climatic conditions and even a certain psychic quality, the purpose for which the town exists, should be taken into consideration in deciding upon its constructive ideals.”1 Within these productive constraints, she focused her design intentions on the individual.

1. Austin, Alice Constance. October, 1916. Building a Socialist City. Western Comrade. 17.

Image 1: Alice Constance Austin, plan of a sector of the Llano townsite, showing community center, parks, educational buildings, streets with row houses, “track for automobiles,” c. 1916. Dolores Hayden, Seven American Utopias: the Architecture of Communitarian Socialism, 1790-1975. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1976). 299.

Image 2: Alice Constance Austin showing model of house and renderings of civic center and school to Llano colonists, May 1, 1916. Hayden, 304.

2

2